II.I - Notes on a Conditional Form

From the very first page of If We Were Villains, it’s apparent that we’ve stepped foot inside a tragic play. The events that are unfolding are such that we can guess just how this story goes, we’ve seen it before, after all. Our narrator continuously points out that things are going to get worse, that there’s a reason he’s stuck in prison now, that every action has its consequence, and we are as helpless as our main characters.

But it’s not necessarily a measure for measure (ha) adaptation of Shakespeare’s own work. M.L. Rio hasn’t created a retelling of Julius Caesar (although it isn’t not a Caesar retelling), but then again, she hasn’t written something entirely original either. This story is a strange amalgamation of the best and worst of Shakespeare’s crimes. It’s lovingly stitched together, a remix and an imitation and an homage all in one. And this starts first and foremost with form.

While we will discuss the content of Villains (obviously), we have to make a pitstop in form because unlike other “dark academia” books like The Secret History, M.L. Rio hasn’t written a plain prose novel. So many of her references and allusions depend on the form she’s chosen, which is an interesting alteration of the five act play structure so beloved by Shakespeare himself.

Although the story is written (mostly) in prose, from the beginning you’ll notice that the book is divided into Acts and Scenes just like a play. Each Act begins with a Prologue, where Oliver and Colborne interact in the present day (2007) - ten years after Oliver’s senior year and Richard’s death, ten years since Oliver went to prison - and the subsequent scenes play out the tragedy at Dellecher in real time. While the story isn’t written as a full-out script, there are odes to the medium. Sometimes full dialogue tags are discarded for colons and character names. Frequently you’ll find stage directions disguised as prose sentences, like when a certain character enters early in the play. A majority of the scenes begin with descriptions of the setting, indicating where our story takes place or what the context of the scene might be, much like in a regular script.

As I said, we are witnessing a play, even as it is written in prose.

The implications of this, that this story is simply a play being put on for our entertainment, appear throughout Oliver’s narration in the text as well. With the suggestion that Shakespeare is to blame for all of it, that he’s directing their steps and encouraging them to act out their fits of passion, we the audience start to wonder if the players themselves even have a say in their own story. In some ways this calls fate into question, if there’s something that is denying the actors the agency they so desperately crave, but more than that it suggests that all this is merely a dream of sorts. It feels reminiscent of the closing of Midsummer when Puck reminds us that these visions that we’ve witnessed are just that, a revelry we’ve all delighted in for a few hours.

Of course, in this case, Villains is hardly a joyous story of revelry. It’s more like a nightmare.

But that’s what makes Shakespeare so appealing to so many: at the end of the show, you get to walk away. Yes, Brutus kills Caesar and Hamlet dies and Romeo kills himself, but it’s only a bad dream. The horrors we’ve witnessed, the dark underbelly of human nature that we’ve been forced to reconcile with, they’re meant to stay on stage. Ghosts only appear in the theater…right?

All of this starts to feel a little meta if you ruminate on it for too long.

II.II - [“Is that right? Fuck me. Line?”]

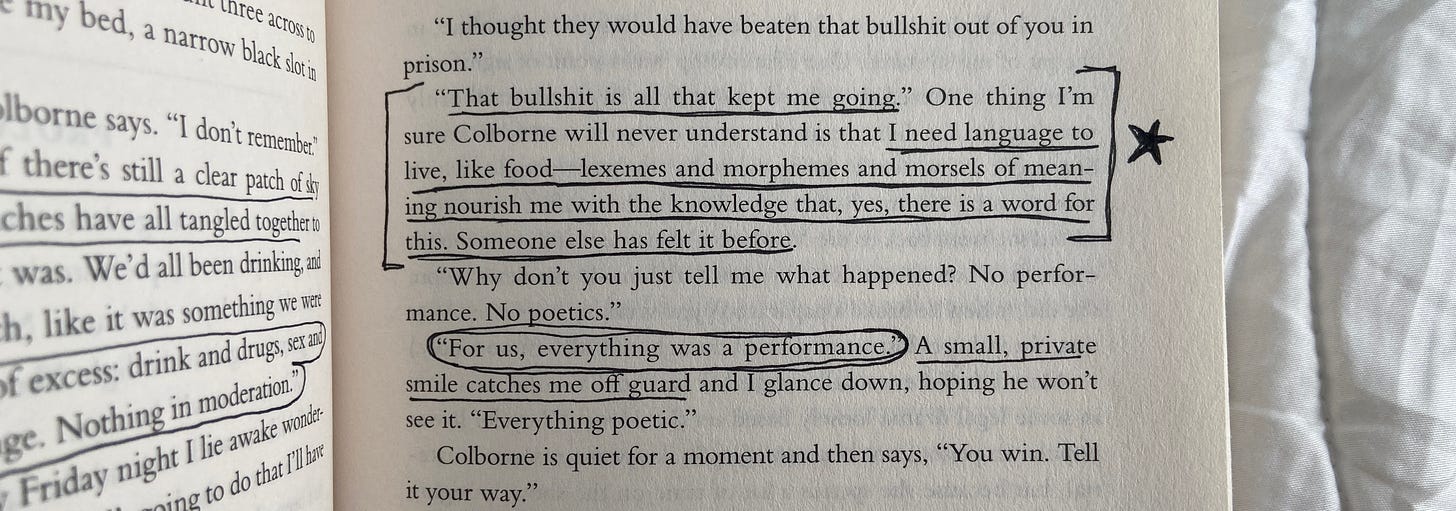

By writing this story as a play, Rio also feeds us another idea: that you can justify anything if you do it poetically enough (direct quote). “Dark academia” already plays around with moral ambiguity, forcing the reader to question just how much evil one person can get away with if their reasoning is sound. In the case of Villains, the main characters’ moral failings can be reasoned away as “part of the script.” Our players appear to be acting under the directions of something(s) outside of themselves, whether that’s Shakespeare or their teachers or Oliver’s narration. (He told Colborne this is the truth, but how much can we believe him? He is an actor, after all.)

And as the story continues, we witness the characters themselves fall prey to their casted roles. Very early on we establish that James is a method actor who gets lost in his parts, but I think all of them get caught up in their roles in their own ways.

Meredith proudly owns her sensuality from the beginning of the story, and rather than shy away from it or change the ending, she recklessly pursues Oliver, consequences be damned. (I find this particularly interesting because I’m certain she knew long before Oliver and James that the two of them were in love with each other…and yet she still tried to date Oliver time and time again.)

In fact, at the very beginning of the story when our players are discussing their strengths in weaknesses in Gwendolyn’s class, they practically doom themselves to the fate of their worst fears. It’s almost as if they’ve become too aware of themselves and their roles, that the narrative punishes them by forcing them to follow such a terrifying script. Meredith is doomed to be seen but never respected and loved for who she is, James is destined to get lost in his method acting, and Oliver, poor sweet Oliver, will always be the most generous person on stage.

(The only person who might escape their fate is Fillipa, who seems to be the one person with a truly happy ending, even though her friends are suffering.)

How much of this tragedy is due to the main characters’ own flaws or desires, and how much of it is destined and fated by The Author, by The Show, by the Play itself? By Shakespeare? Free will loses its power when you’re forced to do the blocking that is handed to you by the script.

If your friend jumped off a bridge surely you wouldn’t follow him, but what if that’s what was required of you to make the show go on?

And sure, we all know this is fiction. It’s a story.

But we’re poets. It’s so much more than that.

As Oliver insists, it’s a performance.

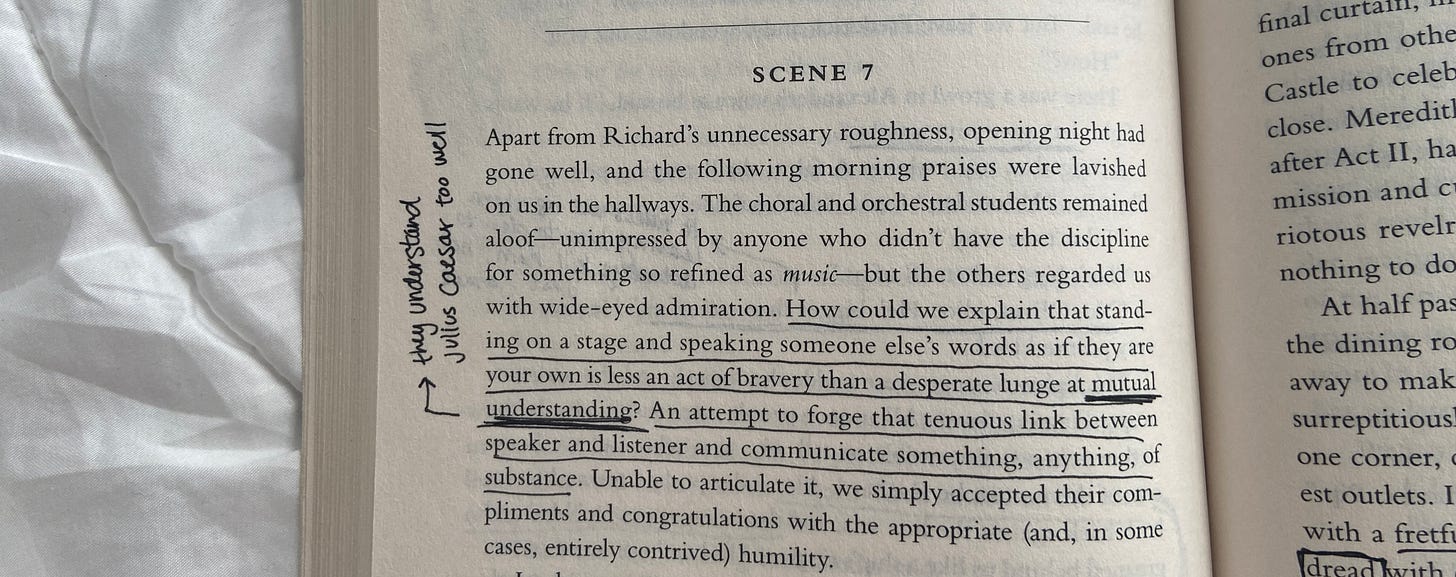

The implication that we’re witnessing a play, that somewhere this is all playing out as lines in a script, characters on a stage, adds a layer of drama and self-awareness that would otherwise be missing. The text lives and breathes, and it asks us questions as we engage with it.

If this is a tragedy, are the players aware of the lines and parts they must play? Are the characters’ destinies merely the actions doled out by the playwright? Would they choose to act differently if they could be their truest selves? Would they choose to act differently if they knew what was going to happen? Surely the answer to the last question is no because I do believe that most of them knew what they were headed towards. Perhaps they wished it would end differently, perhaps they believed that they could change the ending, but they were fully aware of the fates that awaited them.

Maybe this book is proof that we are all actors, that we pretend that the parts we play in our lives are dictated by us, and yet we are still forced to conform to this grand production we are apart of. Perhaps even now, Shakespeare has some hand in our fates.

I’ll admit, it took me an embarrassing five reads (look away) before I finally remembered one of Shakespeare’s most famous lines which appears in a Jaques monologue in As You Like It. It’s so painfully obvious, so quintessentially Villains, I want to bang my head against a wall.

I could probably write a whole essay about “life as a performance.” This is especially poignant for those of us who are neurodivergent who mask, but I think a large majority of people have learned how to perform in order to survive this life. We perform ourselves all the time, whether that’s something like gender or even our socially acceptable politeness. We pretend we are interested when people talk about the most boring things, we pretend we hate that movie that we secretly loved, we try to be more extroverted at our new job so we’ll make friends. Every second of the day we are putting on a performance, and it’s easy to get trapped behind a mask if you aren’t careful.

I’d imagine it’s even worse for actors, especially when those actors have to put themselves through hell for a production.

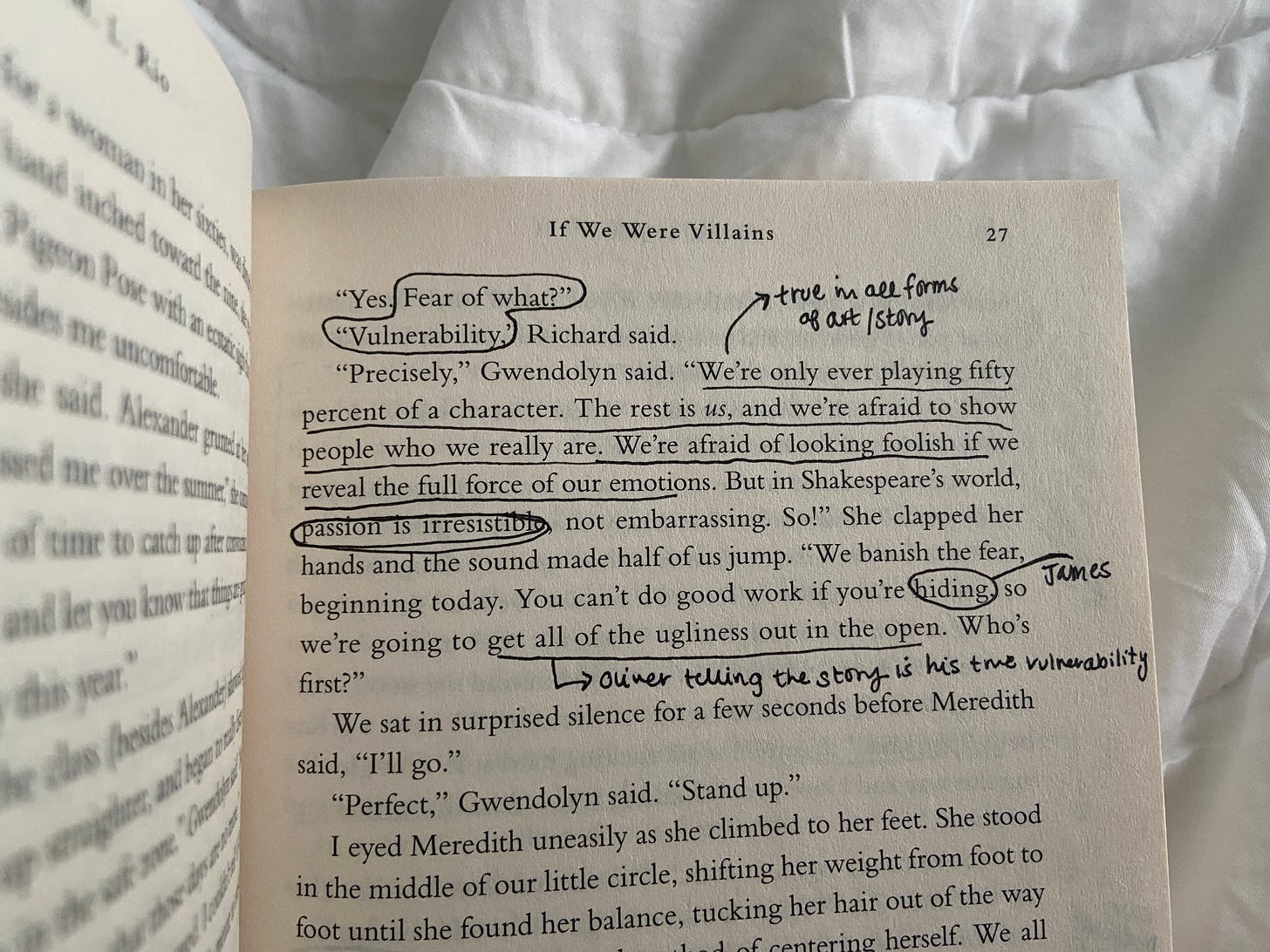

When Gwendolyn talks about acting, how acting is about more than just perfectly stating the lines on a page, she insists that the actors are putting parts of themselves into the text when they perform on stage. They are connecting with the story, even if it’s purely through emotion and passion.

This is why the play within a play is so interesting: the students did not have to go so far as to murder one of their own, to mirror Julius Caesar in all its glory, and yet the passion was there. Shakespeare and Gwendolyn and the art itself pushes them to their deepest feelings, their darkest vulnerabilities, and in the end, they are unable to hide from their truest selves. When they come face to face with their reflections, they find that each of them in turn is a murderer, if only by happenstance. They understand tragedy more deeply than they ever expected to.

But is this because they have the capacity for murder within themselves or because they put on a mask and forgot to take it off? Or is it some strange combination of both?

We already discussed how these students steal Shakespeare’s words for their own in everyday conversation, but we can take this one step further and consider that all their lines are scripted. If we’re reading a play, or even just a work of fiction, the characters themselves are fabricated. Are any of the words or actions spoken by these characters authentic? Does it really matter if they are so long as we are entertained and the tragedy is played out?

Perhaps there isn’t a difference between the characters and the players…but maybe there is. I’d argue that the distinction arises in this final year of schooling. That perhaps the players themselves - Oliver’s true friends, the loves of his life - existed in reality in those first three years of happiness. In this final year, the players find themselves masked and chained to the play they must perform. They embody the characters, give into this spirit of darkness, but are nothing like the players and friends of Oliver’s youth.

In many ways, Oliver himself is the playwright, telling us this story of his past while existing in his present. It’s the story he’s told himself in prison these past ten years as he sits on a hoard of secrets, as he quietly counts down the days until he can finally see his person again. And when he finally tells the story one last time for Colborne, it’s as if he’s calling together all his ghosts for one final performance. He’s handed out bind-ups to the friends in his memory and said yes, these are the words you should say when we plan the assassination. Here is what Shakespeare wants for the actual murder. Enter stage left, exit pursued by a ghost, don’t forget your lines. We’ve a show to perform. And it’s a fucking tragedy.

More than anything, I think this form highlights the cyclical nature of tragedies. The reason it is a performance is because it’s a ritual. It’s a prayer sent up to the heavens, that oh god maybe this time things will work out differently. We watch these horrors unfold hoping that perhaps the script has changed, maybe we’ve casted these characters incorrectly, what if they can overcome their flaws and circumstance? Of course, they never will. That’s the tragedy. But in separating the characters from the players themselves, there’s a distance there that allows for reflection. We can inspect the story for every possible vantage point, can track the exact downfall where things went wrong, and each time we can focus on a different possibility. Just like I’m sure Oliver did every day he sat in that jail cell.

II.III - The Play within the Play

Rio utilizes one of my favorite tropes: play within a play. This is common in Shakespeare - Hamlet and Midsummer are great examples - and often these plays that are put on or watched by the characters add commentary about the play at large. There is intentionality and a deeper meaning behind these productions, and it’s no different in Villains.

If we can argue that Villains is a play, then the play within the play is Julius Caesar. (Or is it Macbeth? Romeo & Juliet? All of the above?) The students spend their first semester putting on Caesar, with Richard as the titular role (surprise surprise) and James cast as Brutus. Acts 1&2 focus on this play as the students prepare to put on their fall production, and we watch as a group of friends slowly begins to unravel as they dive deeper into the text. This dynamic is further exacerbated by the performance of others plays; on Halloween the group puts on Macbeth where James is cast as the lead. At Christmas, after Richard’s death, the group puts on Romeo & Juliet. In the spring, the play they put on is none other than King Lear.

All of these plays within the play coexist and collaborate to create our tragic atmosphere. Would the events of Villains have happened if their senior year wasn’t destined to put on a tragedy? How would the story have played out differently if they’d put on Hamlet? If someone else was cast as Caesar? Would we have witnessed Richard’s fall if the teachers hadn’t casted James as Macbeth on Halloween? Or was this all destined to fall apart regardless of circumstance? Would they have met their demise in the spring when they put on King Lear?

(Did they actually perform Julius Caesar or does Oliver’s story merely use Caesar to help explain their compulsion to leave their friend to die?) ((Sorry, I promise I won’t suggest that Oliver made the entire thing up in his head, I’m just teasing.))

It’s a genius bit of writing because on the surface, yes, a lot of the implications are obvious. Of course, Richard is Julius Caesar. Of course, James is Macbeth. But if you dig deeper, you’ll find there’s so much hidden beneath the surface. Is there a difference between James acting as Macbeth or James acting as Brutus? (More on that later.) Yes, so much of this story follows the plot and themes of Julius Caesar, but couldn’t we argue that this is a reimagining of Romeo & Juliet? (More on that later.) Depending on your knowledge of Shakespeare and his plays, you can find a great many parallels and connections, some of them supremely obvious, but most of them lie hidden in the fabric of the text.

And we’re gonna go digging.