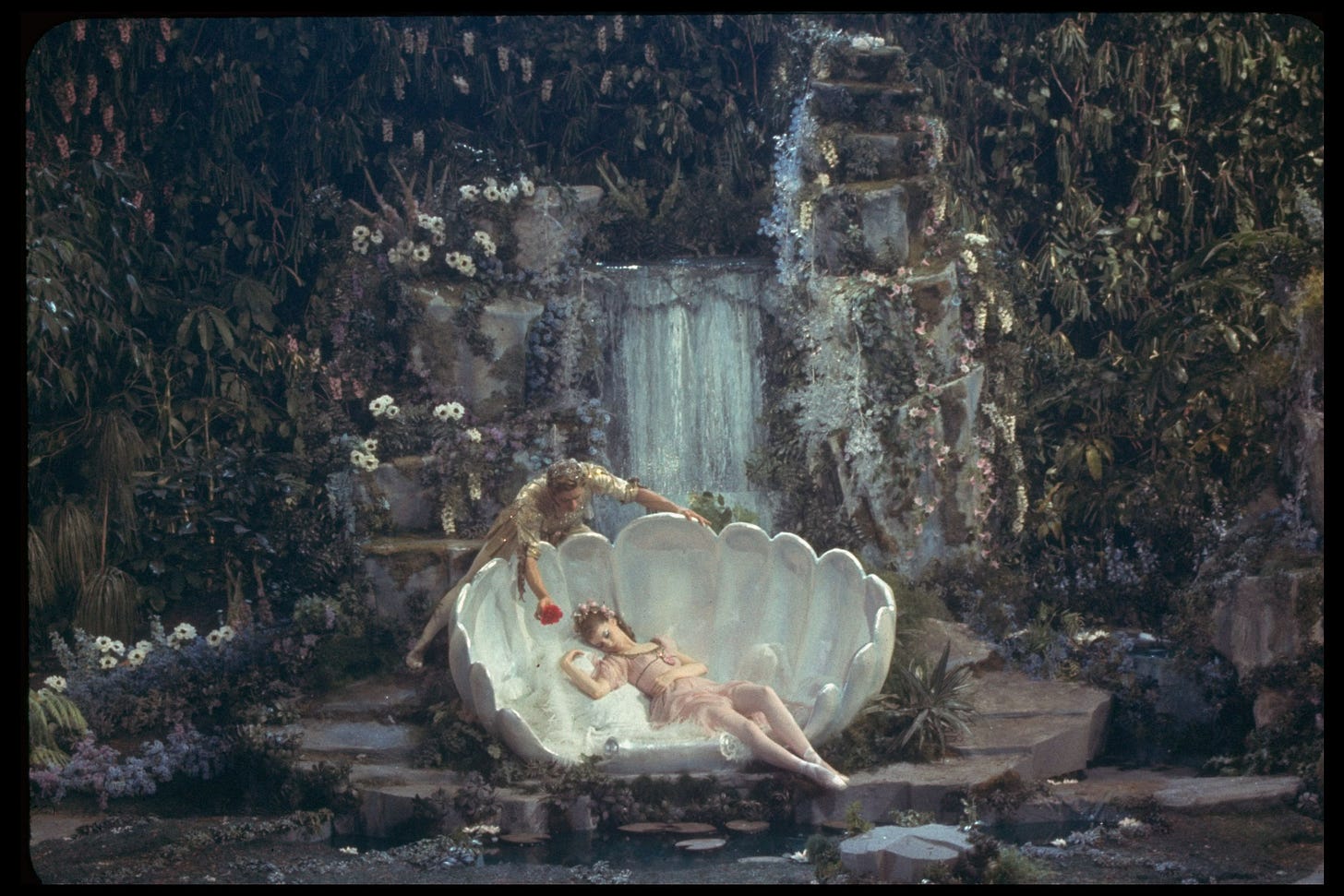

if we were villains (prologue)

part one of an essay on m.l. rio's bestseller - INTRODUCTION

prologue

Although I’ve been out of school for seven years, I still find myself fascinated by campus novels. While most people refer to these types of books as “dark academia” (or, alternatively, “light academia”), these are simply and most broadly books set at school. Specifically, a real campus novel should be about academics too, but a lot of people tend to forget that or ignore it completely. These stories often involve students as they embark on an academic career, as they work tirelessly at their field of study, as their interpersonal relationships start to crack and change under the pressure of campus life.

Books that fall under the “dark academia” umbrella (rather than just a simple campus novel) are often atmospherically dark (surprise surprise). These stories have an ominous undertone; they’re usually set during the darker months of the year, they frequently include violence of varying kinds, and they tend to play around with moral ambiguity. (Light academia, much less popular, is tamer and brighter and more hopeful and innocent, as you can imagine.) The internet has chosen to worship “dark academia” for the aesthetic, since we all obviously want to be witches reading our books in the Bodleian and drinking tea with our classmates whom we secretly hate, but there’s more to it than just the atmosphere.

What compels me most about these novels is that they romanticize one of life’s most torturous seasons, to the point that many of us begin to long for academia, even after academia nearly destroyed us. In our youth many of us struggle through hours of homework, writing essays about books we barely read, hoping beyond hope that classes would be cancelled because of a little bit of snow, and yet one simple campus novel and suddenly we believe we’re ready to get our PhD. We long for the community of a campus, for the freedom we have while we’re there. We want to access libraries and art studios and theaters and common spaces. We want knowledge, pure and simple.

Even more interesting, the campus novels we enjoy the most, the ones we romanticize and daydream about, are generally the deranged, dark ones that appear like a tragic nightmare.

Donna Tartt’s 1992 classic, The Secret History has long been lauded as one of the most renowned “dark academia” books in publishing. All sorts of marketing executives use her book to comp new releases, and it seems like many authors try to ride her coattails, hoping their book might just imitate its so-called greatness. The book is an aesthetic goldmine, full of that autumnal feeling, and it follows a group of Greek students as they muddle through that ancient language at their university. Of course, the story goes south early on when we discover that the students craft a murder plot to silence their annoying classmate. (And trust me, he is annoying.)

Maybe it’s just me (it shouldn’t be), but this is not at all like my personal experience at college.

In fact, if we’re talking about campus novels that feel like my college experience, I’d have to compare my time in school with Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell. And while I truly adored that book when I read it my freshman year, while I found the whole thing entirely too relatable and endearing, it never stuck with me quite like the “dark academia” books I’ve read. Fangirl has some nostalgic aesthetics, and it instantly takes me back to my college experience, but it’s almost one-dimensional compared to something like The Secret History. I think a lot of dimension comes down to the moral ambiguity of the characters and the plot.

Fangirl is a straight-forward contemporary coming of age story. There’s romance, there’s interpersonal conflict, there’s personal growth that ultimately creates a happy ending. But overall, it’s a typical, modern exploration of what it was like to be a college student in the early 2010s. Writing fanfiction, eating granola bars in your dorm room, and doing your best to make friends. It’s simple. You don’t have to think too hard when you read it. (Although it is still full of conflict and discomfort!)

The Secret History will make you squirm. It forces you to sit with uncomfortable questions and implications about humanity. What is true good or true evil? Can you justify murder if you have a good enough reason, if the person you’re planning to kill is actually someone that everyone hates? Does your field of study impact your mental health? (We all know that last one is a raging YES, but you know what I mean.)

And more than that, we aren’t just looking at moral ambiguity. “Dark academia” as a genre leans hard into vague metaphors and open-endedness and questions upon questions. Often these books are mysteries in some way - you’re trying to find out who killed whom or why certain things are happening - and even when you’re given most of the answers at the end of the book, you’re still left reeling. More often than not, when I finish a good “dark academia” book, I find myself staring at the wall wondering how to proceed.

It’s almost as if these campus novels lean into the academia (hardy har), forcing you to think critically and come to your own conclusions and prove to the instructor that you have evidence for the things you find in the text. If you refuse to engage with the text, you’ll still have fun, but you’ll miss a lot. There’s context upon context, hidden meanings and secret messages if you look close enough.

Or rather, if the author is generous and talented enough.

But this is why I was always so underwhelmed by The Secret History. I read Tartt’s book back in 2017, and while I overall enjoyed it, I found it lacking. This is such a beloved classic that I expected it to completely alter the way I see the world. And in some ways, I guess it did. It opened my eyes to the types of campus novels I wanted to read, it encouraged me to seek out more books like it. But every book I sought after The Secret History was in an attempt to find the real book that I wanted The Secret History to be. There was potential there for something truly magical, and I felt like Donna Tartt’s version of it fell flat. It dragged. It got boring halfway through until it picked back up again at the end. I wanted more. I wanted to be haunted and devoured and stained by something that would make me feel alive, even as I feared for the character’s lives and souls. I wanted to like the characters.

In truth, what I wanted was If We Were Villains.

When Villains was released in 2017, the publishing hype fizzled out relatively quickly. It was supposed to be a bestseller, the thing that launched M.L. Rio into the stratosphere, and in truth, it just fell flat. It faded away after publication, slipping between the shelves at Barnes & Noble, ruining any chance of the author traditionally publishing a second book. I had seen its cover floating around, and for the longest time I was convinced it was a historical fiction book, something boring.

Thankfully, I was saved by my trusty hero Tumblr. I saw someone posting about it during the summer of 2019, probably showing off some moodboard, and that’s when I discovered that it’s actually a book about Shakespeare. Or rather, college students acting out Shakespeare’s works. I immediately realized my mistake, that I needed to read this book as soon as I was able, and I splurged on the eBook then and there. Then, two months later, I couldn’t help myself and I read it again on audio.

All of this happened before BookTok. Before anyone really cared about “dark academia” beyond the small communities of BookTube and Bookstagram. I spent years hoping beyond hope that M.L. Rio would announce her next work, her second novel or a short story or a grocery list, I didn’t care. Then the pandemic hit and I read Villains again.

And then the hoards found it.

Almost overnight it took on this cult-like quality. People started making recommendations about “dark academia,” and naturally The Secret History was there too, but Villains became popular out of nowhere. I watched this book grow and grow until it had multiple special editions, until it restarted the career that it had destroyed just a few years previously. M.L. Rio rose from the ashes and announced a new short story. Announced that she had a Substack. Announced that she was releasing a novella. Announced. A second. Full-length. Novel.

It’s the little cult-classic that could, and every day I’m grateful that it went viral because soon we’ll have Hot Wax in 2025 and I’m so excited I could throw up.

Part of why M.L. Rio is one of my favorite authors is because she’s brutally honest about her publishing journey. Her Substack is a writer’s bread and butter, and she’s open about her process and her advice, but more than that she has never shied away from honestly telling us her readers that this shit is hard. That she almost gave up. That she almost never got another publishing deal.

But let’s not stop there. The real reason I adore M.L. Rio is because she’s a powerhouse. Her writing is phenomenal yes, but this woman has an MA in Shakespeare studies (insane) and a PhD in English literature. (Not to mention she’s insanely knowledgable about music, but that’s just a bonus.) She’s too smart for her own good, and every time I read her writing (be that a novel or her newsletter) I thank the universe that she has another chance to publish her words. Mostly I thank the universe that I stumbled upon that Tumblr post when I did because I’ve been carrying her Shakespeare nerds in my heart for five years now, and I’m never letting them go.

Much like The Secret History, If We Were Villains follows a group of university students who may or may not have murdered one of their fellow classmates. (There’s no maybe. They do. Although not in the same way the Greek students do in The Secret History.) This troupe of seven acting majors, who strictly study Shakespeare at their liberal arts college in Illinois in 1997, is thrown into turmoil their fourth and final year of school together as they prepare to perform Julius Caesar. We follow the main character Oliver as he recounts the events of that school year to the original detective on the case. It’s been ten years since Oliver went to prison, but he’s never told anyone the full truth…until now.

Let’s be honest. If you’re here, you probably have already read it. Maybe even more than once, like me.

I just recently read it for a fifth time. Oops.

But this time when I read it, I decided I needed to switch things up. I often read it on audio so I can breeze through it to revisit my friends, so the last few times I’ve read it, I haven’t really experienced it. I haven’t engaged with it as actively as I once did. Naturally, for my fifth read, I decided to embark on a journey I should have made years ago: I started annotating a paperback copy of it.

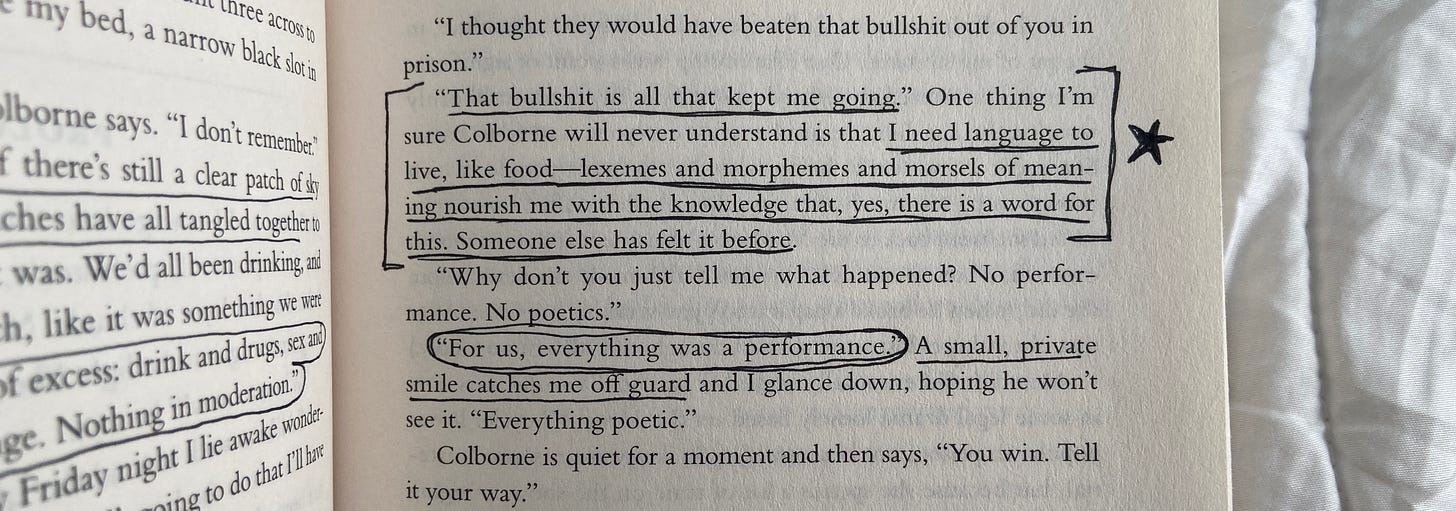

For those who have experience annotating books for personal pleasure, you may agree with me that it’s easier (and more fulfilling) to annotate on a reread rather than on the first try. While there’s joy in highlighting quotes on the first read, and I’ve definitely done that in the past, I find that annotating on a reread (or after four or five reads) gives you so many more opportunities to really dig into the text. The better you know the story, the characters, the themes running throughout, the easier it is to find things you might otherwise have missed. You know what you’re looking for and you know the text well enough to know what’s important, what’s relevant, what might yield a reward.

People annotate their books for any number of reasons — often this is done in an academic setting (surprise surprise), to explore themes or motifs, to dig into the writing and the craft and the language, but for me I see annotating as an opportunity to live between the pages a little bit longer. You get to know an author, you get to befriend the characters, you get to see just what lies at the heart of the story. It makes you appreciate the book in a new way, especially if, like me, you enjoy rereading your favorite books. It’s easy to just keep reading the same words over and over, to lull yourself into comfort because you know a story so well. In order to keep it fresh, it helps to challenge the way you read the words. To engage with the text differently. To research why an author wrote what they wrote and to highlight why it’s effective to the story.

I know writing is intentional, that authors craft their books and imbue them with meaning, but sometimes I forget just how deep a work can be. If you refuse to dive beneath the surface, you’ll never know a writer’s true brilliance.

Villains in particular has yielded incredible results through annotation. I know the story fairly well at this point - I know the beats, I know a lot of lines without batting an eye, I know where it’s all going and what the obvious themes are, but I had never dug into the writing. The text. Which is a bit funny in hindsight because so much of this book relies on the context surrounding it. And by context, I am referring to the Shakespeare.

I mentioned above that the author has a master’s in Shakespeare, and she proves her expertise time and time again. As she writes in her book, Shakespeare doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and this is true of his work but also of hers. One cannot understand If We Were Villains without exploring all the interwoven connections with Shakespeare and his works, and it’s a disservice to both writers when you ignore those parallels.

Admittedly, the reason I never looked into the Shakespeare previously is because I’m insecure about my Shakespeare capabilities. Although I have a history with the Bard (more on that later), I have always struggled to understand him. I know many people feel that way (and that’s why he has so many haters), but for such a long time, I just accepted that I wouldn’t understand Shakespeare unless his words were handed to me on a silver platter. (And by that I mean someone spoon-feeding me a modern translation of the lines of his plays. Usually my best friend or my English teacher.) Ancient English never clicked for me, and I was always very frustrated by it in school. But that never stopped my fascination with him and his works.

For some reason, when I embarked on this reread, pen in hand and Folger Shakespeare Library pulled up on my laptop, things started clicking. I still needed help to parse things out, but I forced my brain to focus on the words and found that I understood more than I used to. I’d gained some critical thinking in the last five years, and maybe, just maybe, I was smart enough to really dig into the text in a new way.

Needless to say, I went overboard. (I always do.)

I learned new things about the Bard but I also learned new things about my Villains. I scribbled frantically and underlined incessantly, and through it all, I decided that the world needed to know my findings. Maybe everybody else has already done this work and I’m just behind, but it’s been far too long since I tried to write an essay (I mean a real, “here’s the evidence” essay) and I’m bursting at the seams to talk about what might be my favorite book of all time.

(Still trying that on for size, not sure how true it is. But it’s not untrue.)

What follows is an extensive, excessive exploration of craft. It’s not nearly as put-together as a real academic essay (I no longer have the patience for MLA formatting or theses or topic sentences), but it is inspired by my time writing about Shakespeare in a past life and acting on stage in an even older past life.

There will be spoilers. There will be too many personal anecdotes. There will be the ravings of a slightly deranged fangirl. You’re welcome or I’m sorry, I’m not sure which is more apt here.

You’ll be unsurprised to learn that when I embarked on this essay, I assumed I could be normal about all this. I thought I would whip up a quick fifteen minute article, wrap it up in a nice bow, and get on with my life. But as we know, I am not normal. I have a special interest, and that interest is going way too far and overcommitting to the bit until it is no longer a bit. It’s serious. So, my quick 3,000 word post grew to be over 26,000 words. And I decided I could not give this all to you in one go. I had to spread it out. I had to do some editing. I had to calm down.

Narrator: She did not calm down.

So you will receive these writings in installments.

I’ve broken it up into a few different acts. (This is part one of seven. Again, I’m sorry.) I decided to spit them all out in a week so I can get in and out of your inbox as quick as I can. For the next six days, you will be seeing a lot of me, apologies in advance.

I hope these musings offer some insight into Shakespeare’s brain and the writings of M.L. Rio. I hope they encourage you to dig into the text, to go see a play on stage, to think more critically about the books you’re reading at the moment. I hope I can encourage you to reread your favorite books, to scribble on the pages, to engage with something for the first time in a long time.

There will be errors probably, but there will be passion, and as we all know, that’s what’s most important here.

Without further ado,

“By the pricking of my thumbs,

Something wicked this way comes.”

— Macbeth, Act IV, Scene 1

ahh isn't reading life the best because I feel the opposite!! I did not understand the point of the long drawn out Shakespeare scenes in Villains for the life of me but I felt every single sentence in The Secret History was important and full of subtext. I think part of it is never having really loved Shakespeare even when I was forced to take three classes in undergrad. Regardless I am excited to hear your take on the novel, I love to challenge my own way of thinking. 🖤